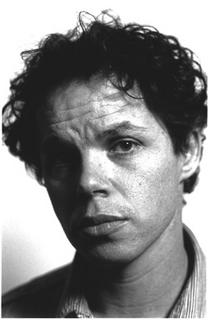

Garth Cartwright

Gypsy Kings

Garth Cartwright and His Journeys with Gypsy Musicians.

"Our empire is surrounded by enemies. Our history is written in blood, not wine. Wine is what we drink to toast our victories." (Anthony Quinn in Attila the Hun)

The above quote is not wholly relevant to the Roma people of the Balkans. But I use it as Hunter S Thompson used it in his new journalism landmark Hells Angels - to describe an endemic outlaw mentality. But also because expat Aucklander Garth Cartwright, who spent many months with the Roma, compares his book Princes Amongst Men: Journeys With Gypsy Musicians to Thompson's first book.

"I chose that because if you don't know anything about gypsies, you're going to think they're wild outsiders who make music and dance and fight and pull knives all the time. And Hell's Angels, if you don't read his book, the only idea you have is of these wild outsiders who ride motorbikes and pull knives. That book of his is a great piece of journalism, and it shows them not as angels in any sense, but it shows them as real human beings, and that's what I want to show, that the Roma are real human beings. They have an incredible culture, and communities, and language that essentially is overlooked."

Cartwright, who grew up in the cultural vacuum of Mount Roskill, wandered through Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia and Macedonia over many months during 2003, tracking down and hanging out with the gypsy musicians. In the marginalised Roma communities, musicians are more than just entertainers; they reflect a culture that is many centuries old. Moreover, they are a celebration of it. It is often the downtrodden that have the best tunes - just look at how jazz and blues, and more recently hip-hop, grew out of African American oppression. Some of the Roma musicians are stars, some are legends, while the majority make their living playing at weddings and festivals.

The Balkans - a war plagued, almost forgotten corner of Europe - is a strange place for a kiwi boy to end up, covering something as seemingly arcane as gypsy music. "When I got to Europe in the early ‘90s I started hearing European gypsy music," explains the London dwelling Cartwright. "It just knocked me over straight away. It's a music that knows no rules, and is sung by people who are really possessed, they don't want to do it politely, or just for the top 40, but just communicating really deeply, there's something beyond just music or entertainment or the trivial background soundtrack that so much music is today. So for someone that just loves music it just grabbed me man, and took over straight away."

It was a convoluted path that led Cartwright to the Balkans. He says he was always interested in reading news about such exotic places as a kid in suburban Auckland. The stifling boredom and lack of cultural stimulation in Mount Roskill - "It was what you'd call a dead zone" - triggered some kind of wanderlust, and he hasn't stopped yet. After immersing himself in music, literature, skateboarding, even boxing to stave off the ennui, Cartwright took to Kerouac-style aimless hitching as soon as he was old enough. He dabbled in punk, and started writing.

Soon enough he was writing controversially about New Zealand art. Hell raiser artists such as Philip Clairmont, Tony Fomison, and Allen Maddox were around, and no one was writing anything engaging about their work. Cartwright lived with Fomison for a spell, before winning some journalism awards that afforded him the opportunity to travel overseas.

"I jumped on a plane and went straight to America, 'cos I wanted to go and hear as much blues and soul and honky-tonk country music as I could. I really wanted to do an On The Road trip. I met an old friend in LA, and we bought a $600 Buick, a rusty old car, and jumped in it and drove down to New Orleans. And continued driving for the next 6 months. Then I went to Mexico and Guatemala and Belize and Cuba, and I did my Latin American wanderings. Then I came back and lived in San Francisco, and essentially I had a real romantic engagement with American and Latin American culture. But to get into the States I had to have a ticket out, so I had a ticket to London. And living in there when Bush Senior was in power and the first Gulf War was on made me think, well, America's not quite as romantic as I thought it was."

On the other side of the Atlantic Cartwright did what he needed to pay the rent, including a stint in market research - "it's a nightmare job you know". It was at this job that he found out he had won a Guardian music writing competition, that he had entered and then promptly forgotten about. "I got a phone call one day, it was this really posh English guy who goes 'I'm ringing up to tell you you've won the competition’. And I'd just had a smoke at lunch time and was like 'Yeah? What's this man?' I didn't really know what was going on, and it took some time to sink in."

Making the most of this opportunity gave Cartwright a rare entry into the closed world of British print. Since then he's written for many daily newspapers and music magazines. And it was through the freelancing that he found the seed of Princes Amongst Men, writing an article on Romanian Taraf de Haïdouks for the Telegraph. But it's not easy making a living out of freelancing, particularly when your preference is to cover a music that loses its cultural context away from its own shores.

"All the media is very parasitic, it feeds on its own media. I think the band of the moment is Interpol, so they all do features on Interpol. They're very much lemmings in that sense. So if you come in and go, 'Look, I've got this story about a woman gypsy queen in the Balkans, and she's been twice nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize, and she's a great humanitarian, and she was friends with Tito, and Indira Ghandi", you'll generally get a blank look. Because even though it's a great story, they want what they've been told is fashionable. I have little respect for parts of the British press. The arts coverage is generally pretty poor. It's an extension of the fashion pages."

Having said that, it seems Princes Amongst Men has been generally well received. The book is part hung-over travelogue, part musicological adventure, and part amateur sociology in the classic New Journalism vein. It tells the hidden story of the Roma, how they live their lives on the fringes as they have done for eons, damaged but not destroyed by the horrors that have gone on around them. But as you would hope, it is the music that shines through like a triumphant beacon. This is equally to do with Cartwright's outsider passion for it, and the fact that it is in the Roma blood, a connection to their past, and a promise for their future.

"They've always been a marginalised community, so music would have always been seen as a way of getting some respect and making some money for your family. It's a community conveying through music and dance their absolute belief in themselves. It's really a deeper, older, more ancient thing. And that's something you realise about the Balkans, it's where Asia and Europe are blending. In Western society we've cut off our roots and built these big urban societies where there's just manufactured entertainment for us."

It wasn't an easy thing to do either, traveling through these shattered remains of Communism's lost ideals. Public transport is average, hotels don't exist, the food is different, and breakfast is generally alcohol and cigarettes. It takes its toll.

"It absolutely destroyed me. The Balkans is the extreme opposite of New Zealand, not in landscape or climate, but in lifestyle. People smoke really heavily, drink hugely - often first thing in the morning someone will pass you a glass of rakia (brandy), it's just their way of starting the day. And fried meats and stuff, there's none of this idea of being health conscious. And when you're living amongst gypsies, you do as them, it's no use standing off and trying to live this healthy lifestyle. If you're along for the ride, you have to go for the ride. That was really hard, and it gets really hot in the Balkans, it's incredibly hot and humid and dusty. Then in the winter it's freezing. It beat me up essentially. By the time I got back to London at the end of September 2003 I was physically shattered. I was lucky I had everything by then to start writing the book, because I couldn't have kept traveling any longer."

Since the completion of the book, Cartwright has been researching his next project about his first love, American blues and soul. If it's anything like as good as Princes Amongst Men it'll be a coruscating read.

Garth Cartwright

Princes Amongst Men: Journeys with Gypsy Musicians

(Serpent's Tail)

Gavin Bertram.