Coming Alive Again

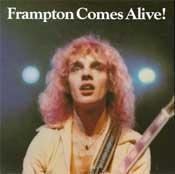

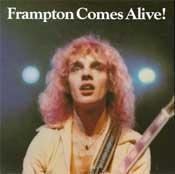

Ah, the excesses of the Seventies. The muscle cars, bell-bottoms, double live albums in lavish gatefold packaging - perfect for skinning up on. And no live album is more synonymous with the era than Frampton Come Alive. This slab of classic rock history was the highest selling album in 1976, going on to reach over 12 million sales.

This world conquering success came as a surprise, not least of all to Peter Frampton, who had been involved in the music business for well over a decade in the mid-1970s. Having achieved relative success with both The Herd and Humble Pie, the overnight success tag did not sit comfortably, and neither did the fact that he was suddenly the biggest act in the world.

Frampton had difficulty dealing with this success, and with the attendant record industry bullshit. Management and record company interference and greed, some bad decisions, and a horrendous car crash ultimately moved the spotlight on, yet he remains in the game.

For someone who once ruled supreme over the world's music charts, Frampton is particularly friendly - and approachable. This interview was arranged virtually overnight, which is a pleasant change from chasing people around the globe for weeks or months. About to embark on a Floridian holiday with his daughter before heading to Australasia in May, Frampton is relaxed, humorous and charming when we speak on the phone. This too is a pleasant change.

There are various reasons why Frampton is heading to the antipodes, despite having been off the popular music map for some time. Firstly, it's being billed as the 25th Anniversary tour for Comes Alive, though the timing seems a little off for that particular celebration. But he's also still pushing his most recent album, 2003's Now. And lastly, it's been 18 odd years since he was last in these climes, as guitarist on David Bowie's Glass Spider tour in 1987.

Now is the best of these reasons to go see the show. Generally these types of career revival albums are pale facsimiles of past glories, but not in this instance. For anyone whose only exposure to Frampton has been tracks such 'Baby I Love Your Way' or 'Show Me The Way' from Comes Alive, Now is a revelation. Quality song writing, and not in the mothballed realms of Golden Oldies radio fodder either. White boy blues of the late '60s British variety abounds, and there's a real authenticity about it. But then, as Frampton concedes, Now was a very selfish project for him.

"The pressure of Frampton Comes Alive has long since left, now it's a case of when I want to make some music, I don't even plan it, it happens when it happens. I didn't really think about anything apart from 'Am I going to have fun recording this song? Do I like this song enough that I want to record it? Do I think this will sound good with the band.'"

One of the reasons he was able to approach the album with this freedom was the fact that it was not released on a major record label. In fact, it was released on his Framptone Records label, and distributed in a fairly loose manner. The reasons for this were fairly simple.

"You probably know by now the record industry is in deep shit," he laughs, albeit in a sagely philosophical way. "It's just a fact that as we get to different decades in our careers, especially with the record labels getting in so much trouble as they didn't embrace the internet straight away, that unfortunately they got in so much trouble financially, it's very difficult to get a major label. It was pretty frustrating. But there is a happy ending. Perhaps because I'm still around and that Universal have my entire catalogue, including the Herd and Humble Pie, the next album is going to be on (Universal sub label) A&M Records, which is rather nice."

Now was recorded in Frampton's home studio, the first album he has had the luxury to pursue in that manner. He says he has been saving pieces of equipment for years with that goal in mind. And although he is an analog aficionado through and through, the album was recorded using Steinberg's Nuendo software - a big psychological step for the musician.

"I was very reticent to go that way - but Chuck Ainley the engineer did the aural litmus paper test, recording the same thing in analog and on Nuendo, and played them back together and swapped between the two, and it was very good."

Amongst the highlights on Now is an emotional rendition of George Harrison's 'While My Guitar Gently Weeps', a fitting eulogy to Frampton's good friend. He not only had the pleasure of knowing Harrison well, he also played on his landmark triple disc solo excursion All Things Must Pass. And as Frampton coyly notes, he wasn't even credited for it - though he generously marks this down as a mere oversight. Other than that, he says that recording session remains a highlight not only of his career, but of his life. He enthusiastically recounts this memory, affecting a fair Liverpuddlian accent when quoting the quiet Beatle.

"The best time for me was when we'd done the tracks and George called me up and said 'Phil wants more acoustics on most of it, would you come down and bring your acoustic and the two of us will track away'. Sitting with George in the big room where Sergeant Peppers was recorded, sitting on two stools looking through the glass at Phil Spector. In between changing reels George and I would jam, and I can't tell you what that was like; jamming with a Beatle is pretty incredible. And I got to jam with Ringo during those sessions and later. And of course when it was my turn to start a jam, I started with a Beatles song, because I could! It was just a thrill, it was probably one of the most special moments of my life."

The next highlight of his career was that great rock monolith from 1976, an album that has coloured his life in both positive and negative ways since. Frampton remembers vividly the flash of realisation that Comes Alive was going to be massive.

"I remember going away for a ten day getaway right after the New Year in '76, then it came out March 17th. We had one show booked in Detroit, about ten thousand seats. Here I am headlining there for the first time, and I went away and came back, and we had four nights sold out. That was the realisation, there it was, the album is zooming up the charts and I'm selling out multiple nights in cities, which was unbelievable."

As one would expect, he allowed himself some time to bask in his fame - three weeks in fact. And in some ways it was those around Frampton, those who should have been protecting him that brought him back to earth so quickly.

"This incredible pressure was put on me - 'Okay Sonny, follow that one up!' It was incredibly difficult to do. The I'm In Me record was done way too soon, I wasn't happy with it at all, the record company and management was enjoying my success and their new wealth shall we say. Which I was enjoying too, but the wealth that filtered down to me... that period was marred by some managerial jiggery pokery, meaning I got ripped off royally. It happens to everyone unfortunately, when you're not prepared for that kind of financial gain, there is a lot of people who start taking the piece of the pie. But they don't ask, they just take. That was very frustrating, to say the least. There were a lot of things that went along with that success that were not as good as they could have been. So, the good, the bad and the ugly, and I wouldn't change anything for the world, it's all been a great experience and I'm still playing what I want to play and doing what I want to do. So, I thank myself, for that wonderful record!"

No question then that Frampton Comes Alive has stayed with him like a tattoo. As has much of the audience he gained from it. Frampton says he gets a broad cross section of ages at his shows these days, from those that grew up with that album, to their children, and even their grand children.

"And they're all singing away!" he happily notes. "It's been rather interesting and very gratifying to see that whatever I've done during my career has stood the test of time. Obviously Comes Alive has helped immensely in that area, but people love Humble Pie as well. I have to be very thankful that the audience has broadened over the years - it could have been the opposite and never overflowed into other generations, but it has which is great."

One of the reasons for this is clearly the fact that Frampton played himself on the 'Homerpalooza' episode of The Simpsons, rendering him forever on the greatest cultural compass of the 1990s. He laughs when he remembers Homer's introduction of him to the crowd. "Hey kids, don't trust anyone over thirty! Now here's Peter Frampton."

"When we went to Australia with the Rock Symphony we did a press conference, and the gentleman who was introducing us said 'And the gentleman on the end - I know him because of Frampton Comes Alive and Humble Pie, but my son only knows him from The Simpsons. That was a big thing for me, to hear him say that. I didn't realise how lucky I am - and honored- until that point. It's one of the better written shows on TV, obviously. And doing it was such an incredible experience, because they asked me what I'd say or do in a situation. It was wonderful, that made it real."

Gavin Bertram.